2. THEY CALL IT HOME

2.5 Flora

The archipelago is dominated by one color above all others: green. The natural vegetation in many places is impenetrable to all but the aboriginal population and forms one of the densest rainforests on earth. Only on North Sentinel and Rutland Island is there a more open natural forest without thick underbrush. The nat-ural vegetation contains a least 2315 species of vascular plants ranging from enormous hardwood trees, palms, lianas and many other creepers to canes, bamboo and orchids. Many bear fruit or are themselves edible while others have scarcely-investigated medicinal properties that were known and utilized by the aboriginal Andamanese. The local flora presents a broadly similar picture to that of the faun: of the vascular species only 25% are widely spread over mainland Asia and the Indonesian islands while 10% are endemic. If non-vascular plants such as mosses, ferns and their relations had been more closely investigated, it is certain that a lot more endemic species could be added to the count. Like the fauna, the majority of non-endemic plants show affinities to Burma.

Today, the native jungle is retreating before the chainsaw and the axe. The Indian government has set aside 40% of the forests as Primitive Tribal Reserve, leaving the remaining 60% for commercial exploitation. High-quality timber such as mahogany, teak and rosewood as well as lesser qualities for plywood and matchwood are among the few export commodities of the islands.

When the British arrived to stay in 1858 there were very few naturally occurring coconut trees in the archipelago even though the trees grow readily enough when planted. All of the coconut palms growing in the Andamans today are descendants of trees planted by outsiders. The conclusion that the native Andamanese must have had something to do with this pre-1858 botanical oddity is inescapable. The Coco islands to the north received their name from the abundance of coconut palms growing there from times immemorial and it cannot be mere coin-cidence that these islands were just out of reach of aboriginal Andamanese ca-noes.

To bury a coconut, uneaten, and then to wait a decade for it to grow into a fruit-bearing tree would have been inconceivable to these exclusive hunter-gatherers. Instead, they immediately ate all the nuts the bountiful sea washed up on their beaches. The beachcombing Aryoto groups before 1858 were sufficiently thorough and numerous to ensure the permanent absence of germinating coconuts all around the islands. They searched every yard of the entire coastline weekly and the few nuts that escaped their keen eyesight would be polished off by the ubiquitous Andamanese pigs. No nut had a chance to germinate and grow into an adult tree.

Naval Lieutenant Colebrooke was one of the earliest reliable observers to have visited the islands in 1789-1790. He was the first to note the peculiar absence of coconut palms but he also reported a few isolated clumps of the trees in secluded places. Such isolated clumps are now thought to have marked the hiding places of Malay and Burmese pirates.

As we have seen, the Andamanese fauna and flora presents a somewhat impov-erished version of its counterpart in the Burmese Arakan region to the north. This is an important clue: in the geological past and especially during the Pleistocene epoch the Andamans must have been a peninsula connected to the Burmese mainland a few times or a least an island separated from the mainland by only a narrow passage. The Andamans have never been connected to the Nicobars, still less to Sumatra or the Malayan peninsula. The conclusions that can be drawn from the limited mammalian life on the islands are less clear-cut. It may be that many species did not yet populate the Burmese mainland when the Andamans were cut off for the last time by the rising sea or, alternatively, the Andamanese hunters together with the shrinking area of the islands could have affected the larger more drastically than the smaller animals. It cannot be coincidence that the only sizable animals occurring naturally are creatures of the sea, the species that would not at all be affected by the rising of the sea or very little by bands of human hunters.

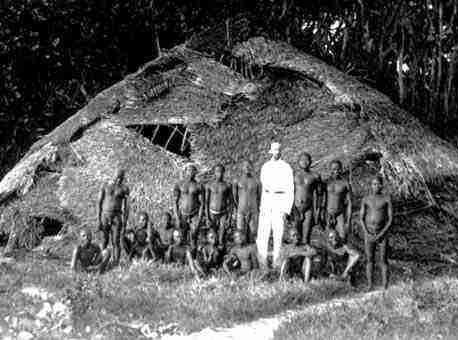

2.6 Andamenese vs. nicobarese populations

Geographically, the Andaman archipelago is not remote. It sits right across several major ancient trade routes, offering mariners fresh water, food and wood as well as shelter from storms and competitors. Generally, oceans are more likely to bring together rather than isolate prehistoric as well as modern human populations. Given an elementary boating technology and minimal navigational skills, it is obviously easier to travel along a river, a coast or even across the sea than it is to hack one's way through thick jungle.

It is therefore all the more surprising, to say the least, to find the Andaman islands and their aboriginal population largely untouched by the outside world far into modern times. The neighbouring Nicobars are so similar in so many ways yet their population, apart from the Shompen, does not resemble that of the Andamans in any way. The Nicobarese boast of an ancient, totally different and far more advanced technology and culture and they are not Negritos. No really convincing explanation can be offered for this remarkable state of affairs. We can only note for the Andamans that a combination of dangerous coral reefs, an al-ways unhealthy and sometimes violent climate and the vicious hostility of the aboriginal population towards intruders seem to have been sufficient to keep the outside world away for thousands of years - until 1858.