1. CONTACT

1.4 The Sentinelis are the most isolated people in the world.

Why give so much space to the Sentineli, least known and least accessible of the surviving Andamanese groups? Why not introduce the Andamanese through the pacified and much better-known Onge? Or through the Jarawa, now so often in the news?

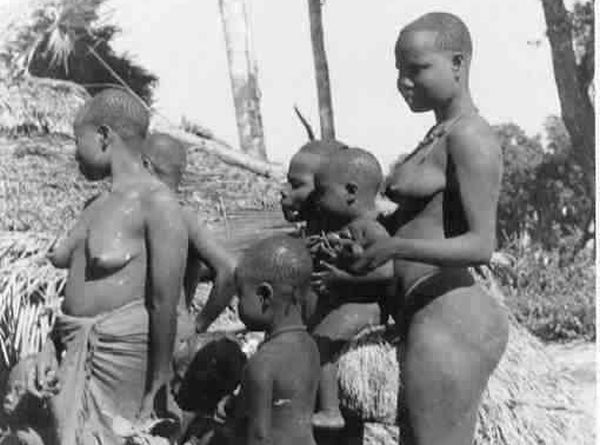

The Sentinelis are the most isolated people in the world. They are isolated in a way that all Andamanese have been until the early 19th century. It is an isolation so profound that is virtually inconceivable in a global village of jet travel, satellites and worldwide webs. The Sentineli still live as the ancestors of mankind lived during the warm interglacial before the last ice age (Eem-Interglazial 130'000 – 80'000 years). Even the few remaining tribes in the interior of New Guinea and the Amazon jungles that have never yet seen a visiting anthropologist's ingratiating smile, are technologically more advanced and far better connected to the outside world than the Sentinelis.

1.5 Hostility inbetween andamanese groups

There were some Greater Andamanese Aka-Bea tribesmen on this first of Portman's expeditions and they warned of the Sentinelis' hostile intent. The British did not at this early time appreciate the many and complex enmities existing among the natives. To increase the confusion, the Andamanese themselves were not too clear about other groups who were not their immediate neighbors. The Aka-Bea on this trip may well have confused the Jarawa (who were their neighbors and enemies on Greater Andaman) with the Sentinelis (who almost certainly had no previous contact with the Aka-Bea). Taking Aka-Bea along was counterproductive and may actually have strengthened Sentineli hostility. In 1974 there was a repetition of this scene when the Indians brought three Onge tribesmen (who are thought to be much more closely related to the Sentinelis than the Aka-Bea had been) to the island but found them of little help. The Onge were terrified of the Sentinelis and the frustrated scientists could not even clearly establish from the shouted exchange between Onge and Sentinelis (the Onge with the boat's loudspeaker at their disposal) whether the latter understood at least a little of the formers' possibly related language. The Onge were too far from the beach to understand what the Sentinelis were shouting back at them while their own amplified protestation of desired friendship in the Onge language did not seem to go down well with the Sentineli.

1.6 The Jarawa tribe

The Sentineli problem has vanished - but not been solved - for the moment because the Port Blair authorities have found themselves in much hotter water elsewhere. On 21st October 1997 they were quite suddenly confronted with the fruits of their own policy: the Jarawa came to town.

Dr. Anstice Justin, head of the Anthropological Survey of India's Port Blair headquarters for many years (and of Nicobarese ancestry himself), had been at the forefront of the struggle to make the Administration see reason. He took the reasonable scientific position that unless there was a rationale behind (and some scientific benefit from) the frequent "friendship" visits to the Jarawa, they would do more harm than good. There should at least be an idea of what to do once that coveted friendship had been acquired. The Port Blair administration did not agree but at least started to require strict medical check-ups from anyone wishing to enter Jarawa territory. There would have been nothing wrong with that - if the regulation had been enforced. The Andamans are full of well-meaning regulations that the regulators themselves ignore when it suits them. Over the Anthropological Survey's protests, these expeditions soon degenerated into "junkets in the jungle" laid on for high-ranking politicoes, their wives and other hangers-on. Health checks could not possibly be enforced on such grand personages and there was less and less capacity or need for scientific staff to come along. Between May 1990 and February 1997, no less than one hundred such "parties" took place, cunningly disguised as official "contact expeditions".

During the 1990s, private enterprise was also possible. One high-ranking official ran a profitable racket taking visitors to shake hands with Jarawa or noisily arresting those who tried to do the same without paying up. The man is now retired but can still be persudaded for a suitable fee to mumble his deep insights and pronounce on the dangers facing his former charges.

One of these junkets in the jungle has been summed up as follows (our comments in brackets; the name of the visiting politico has been deleted since he was only one of many):

The Indian politician --- led a parliamentary committee to the tribal heartland, met some people (Jarawa) wandering on the Trunk Road (cut into the Jarawa jungle reservation against the scientists' advice - but trees in the reservation tend to be bigger than outside and the temptation was irresistible), offered them toffees, suggested giving them raincoats and asked them to pose for photographs.

A particularly unpleasant aspect was what Dr. Justin has aptly called "cultural pornography," an aspect hardly ever reported in the press. The Jarawa cannot tell males from females when clothes are worn and so tend to check visitors by a quick touch of the relevant anatomical regions. Indian society in general (and still more Port Blair society) is still stuffily prudish and expressions of sexuality tend to be as furtive as they have ever been in Victorian England. The Jarawa's innocent behavior caused palpitations among their visitors and mislead some into thinking that they could return the favor in rather less innocent ways. Downright horrific are reported cases of sexual violence (only a small part of which actually comes to official attention of which only a tiny part is ever reported). A bush policeman, said to be "sexually disturbed" shot a Jarawa woman sitting on a tree into her genitals. In what was probably a Jarawa revenge raid for this atrocity, in March 1996 two Indian settlers were killed (one woman with multiple arrows shot into her genitals) and several more wounded.

When Dr. Justin's protests were ignored, he went to the extreme step of taking legal action against a high-ranking member of the Port Blair administration. It did not boost his career: one of the best field men of the Anthropological Survey of India was transferred to a desk job in Calcutta. Meanwhile, the abuses continued. The partying in the jungle has not increased our knowledge of the Jarawa culture by much. After 25 years of such "research", our knowledge of the Jarawa is still pathetically inadequate and there is no linguist with more than the most shaky command of the Jarawa language and no one has ever reported on the Jarawas' belief system. Only in April 2002 has the ASI published a work that does begin to publish serious research (Jarawa Contact: ours with them, theirs with us, ASI publication no. O.93, editors K. Mukhopadhdyay, R.K. Bhattacharya, B.N. Sarkar, Calcutta 2000). And about time, one is tempted to say.

When the Jarawa started to leave their jungle homes and to come into Port Blair in October 1997 to demand food and free gifts, the Administration's pidgins truly came home to roost. Even to remote observers it was painfully obvious that they did not know what to do. The Andaman Tribal Welfare actually went so far as to suggest an air-drop of "seeds to replenish (the Jarawa's) plantations" (for complete and utter hunter-gatherers such as the Jarawa, plantations would certainly be a high priority for replenishment...). This ludicrous proposal throws a realistic light on the quality of "scientific advice" being bandied about within the local administration.

It is widely thought among the Indian settler population of the Andamans that the Jarawa had started to come into town because they could no longer feed themselves. This is not so - but the belief was encouraged by officials to detract attention from the real cause. True, the Jarawa hunting grounds are shrinking and are threatened by poaching drom settlers, their fresh-water resources are being diverted to the settlers' fields and their forests are being cut down by loggers in cahoots with the authorities. The Jarawas' long-term survival is indeed threatened by encroachments from all around and from within their reservation but there is no shortage of traditional resources in the jungle at present. What really happened was that the Jarawa had grown used to the flow of free gifts (including toffees and raincoats). They employed the sort of impeccable logic that apparently was beyond the local administration: they thought, if you want more, go to where it came from. And so they did.