1. CONTACT

1.2 The hostility of North Sentinel inhabitants

towards foreigners

For the past century all sorts of people, ranging from policemen to self-important politicians, administrators, naval officers, anthropologists to private and occasionally blue-blooded busybodies, have tried to land on the North Sentinel island and make friendly contact. The estimated 50 to 400 Sentinelis on their 72 km2 island would not hear of it.

The earliest known mention of the Sentineli was published by the British surveyor John Ritchie who wrote down the following observation in 1771:

... and if we may judge from the multitude of lights seen upon the shore at night, it is well inhabited...

Until 1880 no known attempt to investigate the island went further than a circumnavigation of the reefs surrounding it. The islanders themselves were seen only by their torches at night or glimpsed as tiny specks on the beach from afar. In 1867 the then Officer in Charge of the Andamanese, J.N. Homfray, sailed all around the island but refrained from landing after he spotted natives only too clearly looking forward to slaughtering him on arrival.

In 1880 an expedition under M.V. Portman successfully accomplished the first known landing on North Sentinel island. It stayed for a fortnight. As the Sentineli would do so many times later, they avoided the unwelcome visitors by simply vanishing into the jungle. A woman and four children were nevertheless captured by chance and kept for a few days aboard the expedition ship after which the woman and one child were loaded with presents and released. A few days later, an old man, his wife and child were also caught and they with the three children from the earlier "bag" were brought to Port Blair for observation. There, as so often happened with captured Andamanese, the two adults sickened and died within a few days. The children were hurriedly returned to their home island, given presents and released. As Portman himself admitted later, this was hardly the right way to go about establishing friendly relations. Rather unconvincingly, he blamed lack of reliable intelligence for the unfortunate tactics and took a little revenge on the elusive Sentinelis by describing them as habitually wearing a "peculiarly idiotic expression" .

It is rare in the 20th century for the representatives of a sovereign government to wade ashore on a small tropical island in order to place cheap baubles on the beach, only to withdraw again in some haste, looking for arrows from the natives known to be lurking in the bushes. Most would connect such a scene with the Age of Discovery, with Columbus, Vasco da Gama or Captain Cook. When, moreover, visiting royalty is prevented from landing by a lone warrior on the beach, the story must surely come from the realms of fantasy. Not so!

Precisely this scene took place in 1974. The island so difficult to approach for king and commoner alike is North Sentinel in the Andaman archipelago. Ex-king Leopold III of Belgium, attended by the chief administrator of the Indian territory of the Andaman and Nicobar islands, in that year made an unsuccessful attempt to land there. The royal party was faced down by a lone warrior armed with bow and arrow and clad in nothing but a scowl and a few personal decorative items.

Indian exploratory parties under orders to establish friendly relations with the islanders have made brief landings on the islands every few years since 1967. Unencumbered by security worries for a royal dignitary, they could take higher risks. Their usual reception, however, was just as unfriendly as the one for the king. It was all the visitors could do to place gifts of coconuts, plastic buckets, iron tools and other marvels of modern civilization on the beach before they had to scramble back into their dinghy, sometimes under a shower of seriously hostile arrows. Blood was drawn at least once, in March 1974, when an arrow met its mark in the left thigh of the visiting team's cameraman. On seeing that he had scored a hit, the marksman on the beach laughed happily before stalking away to sit proudly in the shade of a tree. He clearly considered that he had done his duty by his people, as indeed he had.

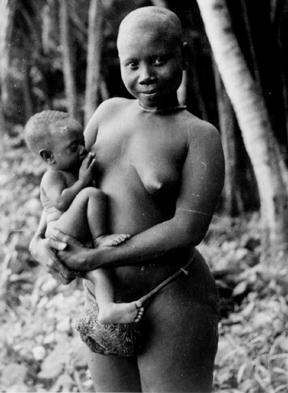

To return to Portman's expedition: it is rather out of character for him to have left us no report on his Sentineli expedition. All that we have been able to find are a number of photographs kept by the Anthropological Survey of India at Calcutta. These are of little scientific value since all those that depict more than just vegetation show Portman's Aka-Bea trackers as "Sentineli" in what Portman must have fancied "typical situations" such as cooking, sleeping, keeping on the lookout for enemies. Portman obviously let his imagination run free and allowed his Aka-Bea poseurs to ham it up to a quite hilarious degree. Entertaining as these photographs are, the lack of any surviving report on the scientific findings made by Portman's expedition is rather unfortunate. Today, little more is known about the Sentineli than was in 1880.

The second recorded landing on North Sentinel island was brought about by a very unusual event. Beginning at nine in the evening of 26th August 1883 distant gunfire was heard at irregular intervals and this was interpreted as the distress signal of a ship. On the morning of the next day the same Portman went out to search for the troubled vessel in the area of Rutland Island, the Labyrinth group and North Sentinel Island. He landed on the latter but found only deserted villages and no sign of a distressed vessel. The natives had melted away again in the face of superior numbers and firepower. The landing party left gifts and then returned to Port Blair. The gunfire continued, streams dried up briefly and the sea receded and advanced several times in a most unusual way. Only when the telegrams arrived did it become clear to the bewildered officials at Port Blair what had happened: the "gunfire" was the final volcanic cataclysm of Krakatoa, exploding 2500 km (1500 miles) away near Java.

North Sentinel island is not only defended to this day by its warriors but also by rough and unpredictable seas, aided and abetted by a nearly unbroken ring of treacherous coral reefs. The reefs make the island all but inaccessible by sea for 10 out of 12 months and fairly dangerous to approach during the remaining two. The island has long been known and feared by sailors for its manifold defenses. Decades would pass between visits, with the Sentineli living their simple lives dreamily undisturbed - for the moment.

Unrecorded successful landings are likely but they cannot have been numerous. Occasional poachers landing on the island and contributing to the continued hostility of the Sentinelis are a distinct possibility. It would be one explanation for the inexplicable changes in Sentineli behavior from one visit to the next, almost friendly one time, violently and implacably hostile the next. Shipwrecked sailors may also have caused trouble on the island from time to time throughout its history. As late as March 1970 a wreck was spotted on a coral reef off the SE coast. On inspection it was found to have been lying there for 7 or 8 months. There was no sign of the crew. At least one escaped Indian convict from Port Blair is known to have made his way to North Sentinel Island in 1896. Two others with him were drowned on the reefs surrounding the island. The lone survivor's luck did not hold: he was killed by the Sentinelis and left on the beach where his body was found by pure coincidence by a visiting British party.

None of the recorded landings prior to the 1990s had been successful at establishing friendly relations. The Sentinelis had first demonstrated their standard pattern of avoiding visitors in the 1880s and were still following it in the 1990s. Small visiting parties were seen off on the beaches. Whenever a larger number of visitors threatened a landing, the islanders took to their forests and did not return home until the intruders had left. Gifts left behind initially seem only to have fed suspicions. The Sentinelis may never have heard of Greeks but they clearly understand the ancient warning of Greeks bearing gifts. As Indian anthropologists admit privately today: how right they are!

Today, more than a century after the first known landing, the Sentinelis are still the undisputed lords of their island. British India has long since faded into history but the writ of independent India applies to the island only in the sense that it has erected a territorial slab on this oddest speck of land under its sovereignty. Repeated gifts left for them have mellowed the Sentineli a little in the 1990s and a few visits during which landing parties on the beach were not immediately chased away have taken place. But the Sentineli are still on a short fuse. On one occasion a high-ranking official pulled rank on the anthropologists and insisted on staying longer and going closer to the Sentineli than the scientists recommended. Binoculars on the visitors' boats had spotted a number of warriors hiding in the bushes; they made no hostile moves and seemed to be there just to observe the meeting on the beach but their presence was unsuspected by the visiting party on the beach. When that party had overstayed its welcome and even tried to move closer to the Sentineli, an invisible red line must have been crossed. Warning arrow shots were fired while the hidden warriors stepped from their hiding places. In the rush to the boats, the official responsible for the mess was in such a hurry that his boat overturned and he had to be pulled in, dripping wet. This seemed to amuse the Sentineli as much as it did the accompanying anthropologists - though the latter would have been well-advised to hide their mirth. Unfortunately, at that moment the official's armed guards panicked and a shot was fired into the air. This went down very badly with the Sentineli (who clearly knew what guns were for) and seriously hostile arrows began to fly. Luckily for the visitors, their boats by that time were already out of range.

There was a reported plan to set up coconut plantations on North Sentinel island as reported in a revealingly casual way by two Indian scientists in 1990 (one of them connected to the Max Planck Institute in Germany): Recently, there has been some sign of hope for cultivating friendship with the Sentinelese which is pursued by the Andaman and Nicobar Administration. Gifts are kept on the shore which they hesitantly take away. Proposal is also under consideration for the coconut plantation in the island.

The ubiquitous M.V. Portman - otherwise a fairly humane man by the standards of his time and place - shows another side of his character and colonial attitude when he started the evil ball rolling. He suggested that the island should be turned into a coconut plantation and its inhabitants forcibly accustomed to a British presence. In his opinion North Sentinel Island was "admirably adapted" to the planting of coconuts, adding that if the government decide to convert the whole island into a coconut plantation or if, for scientific or other reasons, it is considered that the aborigines should be tamed, then... search parties should go through the jungle and catch some of the male Jarawas [Sentinelis] and should keep them in the camp... they should be given presents and half the number caught should, after a few days, be allowed to return to their villages... if others do not come willingly... they must be captured and this procedure must be persevered in until the majority of the people on the island have spent some days in the camp, are accustomed to us, and find that they are well fed and not injured. Happily, theses ghastly suggestions were not acted upon. When we asked the Indian authorities in 1998 what had happened to the reported plans for North Sentinel island, we received the following communication: