9. OF MATTERS SEXUAL

Rare though adultery may have been during the old days, it was not entirely unknown. Cuckolded husbands regarded and punished it traditionally as a form of theft. As in all societies, including those that regard themselves as the most advanced, it is impossible to disentangle injured self-esteem from jealousy. If an Andamanese husband found his wife in flagrante delicto, his reaction could range from angry words to the immediate murder of both errant wife and lover. However, too strong a reaction could create a feud with the wife's or her lover's family and friends. Since there was no tribal authority to administer justice, it was left to the aggrieved parties to take any steps they thought appropriate, up to and including the murder of the murderer. We merely note in passing that there is nothing in the early sources about unfaithful husbands; we must assume that Great Andamanese wives never caught their husbands with other women.

The following case dates from a relatively late date, after traditional society had experienced traumatic changes and most Great Andamanese tribes were dissolving. It cannot be typical of traditional society but the reversal of roles between wronged husband and wife's lover is unusual. The incident also gives an idea of the relationship between British authorities and Great Andamanese subjects, showing the enormous discretionary powers that colonial officials held over the lives of subjects during the last decade of the 19th century.

In May 1892 a party of Andamanese came into the Settlement and brought two Andamanese who had committed an attempt to murder in the middle Andaman. One of them (they were both bachelors) had an intrigue with the wife of a man living in the same village, and used to frequent the woman's hut when her husband was absent. One day the husband returned earlier than usual and caught the lover and his wife, but, contrary to all the customs of other countries, it was the lover, and not the injured husband, who took umbrage, and the former, assisted by a comrade, fired two arrows into the village, wounding the husband and a child who was in the way, and then went off to the jungle with the other bachelors of the village. The wounds inflicted were slight, but as the comrade had already been concerned in the murder of Orderly Habib, in October, 1885, I detained the two men at my house and kept them at hard work for some years, as I consider this, and flogging, to be a better mode of punishing the Andamanese than sending them to Viper Jail, where they would associate entirely with Indian convicts and learn nothing but evil. I also insisted on both of them marrying, in order that they might be able to appreciate matters from the husband's point of view.

Onge women were seldom if ever left without company: they were either with their husbands or with groups of other women, even when going into the jungle on a call of nature. The practical obstacles to any kind of extra-marital sexual relations, therefore, were considerable. Pre-marital sex was also not easy or common since young women were married off as soon as they reached puberty. Frowned upon by all right thinking Andamanese, human nature being what it is from New York to the Andamans, nevertheless found ways as the following case shows:

In Tokoebue communal hut a young and attractive woman was sleeping with her husband. Another married man living in the same hut stealthily approached her and had sexual intercourse with her. The woman at first thought in her sleepiness that the man was her husband and so accepted him but she was later able to recognize the man. In the following morning she related the incident to her husband. The husband became extremely angry and chased the culprit who fled into the jungle. The culprit climbed on a lofty tree and hid himself among the leaves, but the aggrieved husband searched him out and shot an arrow which inflicted a deep wound in his buttock. The angry husband was soon pacified by the elderly persons of the camp. When the wounded man returned to the communal hut his own wife, instead of taking care of him, scorned him and kicked him repeatedly.

Research into Onge society was conducted mostly by Indian scientists after 1950. They were, on average, a little less prudish than the early British. One particularly daring anthropologist even tells us the favorite position for sexual intercourse among Onge: the woman would lie on her side with her back to the man who would penetrate her from the back. It must be assumed that this position was the traditional one among other Andamanese groups, too: among Onge and among Great Andamanese the female breast has no erotic significance.

We do not know whether or how the Great Andamanese, Jarawa or Sentineli made and make the connection between sexual intercourse and pregnancy. Only the beliefs of the Onge in this respect are known. The Onge ritual of getankare involves the carving of wooden phalli to be thrown into the sea, the selection of trees to be made into canoes later, images of "offensive dryness causing work," of secretion, the collection of honey, of playful interaction between the sexes and a ritualistic imitation of pregnancy. The getankare commences at the turn of February to March. The Onge believe that the ritual alone ensures the pregnancy of women. The male organ is not involved in conception but is nevertheless necessary to unblock the womb from the "wind" created when a spirit tries to turn into an unborn child. If the husband did not copulate with his wife, the exhalation of the spirit would accumulate in the womb, making the pregnant women feel highly uncomfortable. We will discuss the role of wind and weather in the religious beliefs of all Andamanese groups in a later chapter; as we can see from this one instance alone, it is a major role. Although matters of clothing are dealt with in a separate chapter, this is the right place to lose a few words on the Andamanese sense of modesty and shame. Many, especially early observers have accused them of shamelessness on no other grounds than their near-nudity. As such, the accusation is more a reflection of the observers' own cultural prejudices if not narrow-mindedness, than on Andamanese morals. It took an unusual intelligence and insight for a Victorian worthy to admit, as Man did, that modesty and morality do not depend on the amount of clothes worn.

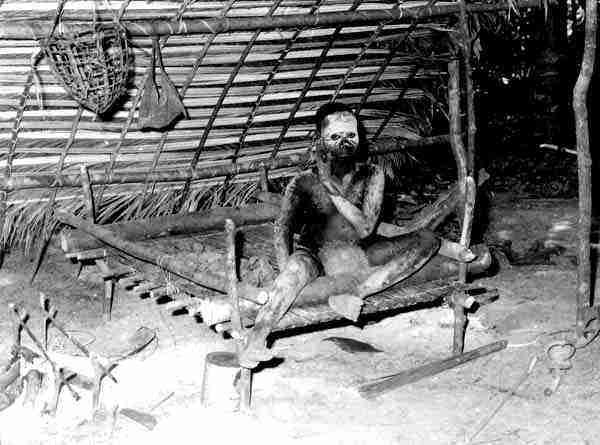

Far from shameless, within their own traditional parameters all Andamanese were strictly moral societies, societies that were so buttoned-up (if that is the right word) that in many ways they would have appealed to the Victorian guardians of public morals had they but seen through all that distracting nudity. Far from shameless, traditional Andamanese women were very modest, almost prudish. A married Great Andamanese or Onge lady would never appear without her genital cover, nor would she dream of removing or replacing it, not even in the presence of a member of her own sex. The Jarawas and probably the Sentinelis seem not to have the same taboo on the female genitals which their few items of clothing do little to hide. We do not know Jarawa, let alone Sentineli, society well enough to do more than note the facts. Based on anthropological experience with other nude or near-nude traditional societies from Africa, South America to Australia, it would be quite wrong to interpret a lack of genital cover as shamelessness. Neither can the remarkable Sentineli sexual activity on the beach as described above be called shameless. All known human cultures know the concept of shame and shamelessness but the concept is applied in different cultures to quite different things, by no means limited to nudity or sexual matters. We do not know what might cause shame in Sentineli or Jarawa society but we can be sure that they know.

The overall evidence, then, points to a fairly but not totally restricted sexual life of the traditional Andamanese. The restrictions seem to have melted away progressively under the impact of outside societies. Early reports of unrestrained lust in the bushes should be taken with a pinch of salt. Victorians of both sexes were used to struggle through life at home and in the colonies buttoned and covered up from head to toe. The near-nudity of their Andamanese subjects must have had an exciting and stimulating effect, especially on male observers that, whether acknowledged or not, could have led to exaggeration. A little wishful thinking may also have been involved.