3. THE TERRIBLE ISLANDS: HISTORY

An expedition to rescue possible survivors and to punish the guilty was immediately decided on. The expedition was ordered to confine its activities to the villages in the immediate area where the crime had taken place and to capture a few Onge alive so that their language could be studied and a means of future communication established with them. The expedition left on the Undaunted and dropped anchor on the east coast of Little Andaman on 11th April 1873, facing the place where the attack had taken place. A force of more than 30 British-Indian officers and men and a dozen Aka-Bea tribesmen were landed in four boats. Leaving behind a guard over the boats, the rest of the force moved along the beach towards the spot where they found the broken boat of the Quangoon. A search of the vicinity produced some blood-stained bits of clothing but no sign of the missing men. The search was widened but nothing was found, nor were any natives seen. By way of punishment, the village nearest the scene of the crime was burnt down. While setting fire to the huts, a large body of Onge warriors burst from the underbrush. A wild fight lasting all of ten minutes ensued which, as the reporting officer said, was decided unsurprisingly in favour of the Enfold rifles. The Onge fled, leaving behind most of their weapons. One uninjured Onge was taken captive and two Indian soldiers wounded with the British estimating Onge losses at between 10 to 12 men. The landing party wisely did not follow the warriors into the jungle but continued to burn down the empty village. While the British were so occupied, a new and larger force of Onge appeared, watched the destruction from afar and then withdrew again, probably because too many had lost their weapons in the earlier fight. Orders accomplished to the letter, the expeditionary force withdrew and, with the usual difficulties, managed to get across the surf and back aboard ship. The Undaunted was back in Port Blair on 12th April 1873.

Because the expedition followed so quickly after the attack on the Quangoon, this time the message was received and understood by the Onge. They did not heed it for long: only a year later, General Stewart was sorely disappointed by the Onge when they showed themselves at their treacherous worst. While waving in a friendly way at the approaching boat, they walked towards it in the shallow water, all the while dragging their weapons along underwater with their toes. The crew of the boat returned alive only because they suspected something was afoot, literally, and did not let the welcoming party get too close before turning back. General Stewart said after this, his second landing on Little Andaman, that the system of making hurried visits of a few hours and at uncertain intervals did little good and that much time and patience was needed if friends were ever to be made of the savages. This was the policy observed by Mr. Portman during the following years, a policy that led to the Onge becoming the least troublesome and most peaceful of all surviving Andamanese by the turn of the century.

3.5 Cruel practices?

On a lower level, traditional Andamanese cruelty showed itself in the way hunted animals were treated and killed; a pig hunt in the islands was not something for sensitive modern souls. The Great Andamanese tribes may have had fewer cruel practices but the reports tend to be less than clear on this point. With the Onge, however, only dangerous animals such as male pigs were killed outright, others were dismembered alive with appalling cruelty. Turtles were roasted alive over an open fire and as if this was not enough, ghastly rituals seem to have been practiced on human captives. The cruelty did not come from the whim of individual sadists but was determined by a ritual designed to kill evil spirits, animal as well as human. Most reports of such cruelties refer to the Onge of Little Andaman but one early traveller is reported to have seen a human corpse burnt to ashes by natives on a Landfall island beach off the northernmost tip of Great Andaman while an incident involving four Bengali fishermen in 1790 has already been mentioned earlier in this chapter. However, quite straightforward killings of pigs seem to have been practiced (33) too, so it is not clear when and under what conditions cruelties were inflicted.

Captive strangers and enemies (which to the Andamanese would have been the same) had their limbs chopped off and, at least on Little Andaman, the still living rump thrown into a large fire around which the natives danced and sang to celebrate the famous victory. It is in the nature of the subject that genuine eyewitness accounts of such fights and ceremonies are virtually nonexistent and when they do exist (as when a scene was observed from afar) would be distorted by shock and disgust.

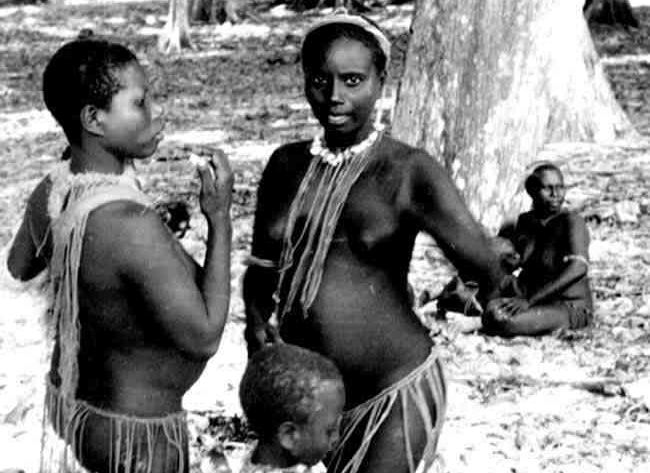

It is easy to see how the ritual slaughter and the dancing around large fires would keep the charge of cannibalism alive for more than 2000 years. Any remaining doubt would have been squashed if a ship's crew had been lucky enough to observe a group of natives wandering on the beach or even establish friendly contact with them: many Andamanese used to wear ancestral bones in the form of necklaces. On Great Andaman they often carried the skull of an ancestor tied with string on their back; photographs exist, showing that this custom was still alive in the late 19th century.

Are the Andamanese guilty or not guilty of cannibalism? Despite all the excited hearsay, the dancing around fires consuming human corpses, the carrying around of human skulls, despite all this evidence, the answer is almost certainly no. Cruel practices there were but no incontrovertible evidence for cannibalism has ever been found. All those who had direct and intimate contact with traditional Andamanese and who in many cases had started out with the belief that cannibalism existed in traditional Andamanese society, ended up firmly convinced that the charge was not justified. Archaeological examination of kitchen-midden also failed to find any trace. Andamanese confronted with the charge were shocked and denied it furiously. Groups at loggerheads often accused each other of cannibalism which at least shows that the thought was not completely novel. The Aryotos accused the Eremtagas and vice versa, the tribes of South Great Andaman accused those of North Great Andaman and everybody, of course, thought the despicable Jarawas capable of absolutely anything. In short, it was always the others. To accuse someone of cannibalism was meant and taken as an appalling insult. A case when an Andamanese murderer had drunk the blood and eaten the flesh of his victims has been reported but such genuine cannibalism was regarded as abhorrent and insane by the other Andamanese.

Summing up the case, it does seem likely that the ancient charge of cannibalism was the result of a misunderstanding of Andamanese rituals as seen from afar by uncomprehending observers as well as the result of horror stories spread deliberately by merchant sailors for reasons of their own.

Before we turn away in disgust from the savage and cruel Andamanese, cannibals or not, a little reflection on the wider issues may be in order. The unconscious cruelty of primitive people has long been known. It is, in essence, a failure of imagination. Primitive people at any level of civilization cannot or will not imagine themselves in place of an outsider. They see only their own limited point of view (which to them is the only possible one), they see only the need to satisfy their own immediate interests and urges (which to them are the only interests and urges that need satisfying). The difference between the natural primitive and the civilized primitive is that the former cannot and the latter will not see a point of view other than his or her own. In this sense, the Andamanese are indeed primitive but are they really that much more primitive than many civilized individuals fighting for their own side in, for example, a civil war?